- 10 min

What is Cubism and where did it come from?

Cubism is without a doubt one of the most important art movements of the 20th century. Where Impressionism started stepping away from the ambition of objectively representing the real world, Cubism took the whole notion and threw it out the window, breaking the glass in the process.

While not many artists persisted with the style throughout their careers it has been a stepping stone or gateway drug 😉 to further experimentation for many. The radical break that Cubism allowed became a door wide open to continue exploring ideas further and further away from representative art, all the way to complete abstraction. It is, however, worth remembering that Cubism itself never became a fully abstract style, no matter how many different viewpoints you can see in a Cubist painting they are still viewpoints of a real object you can recognize.

Here you can look at Georges Braque, Houses at L’Estaque painting created in 1908, now owned by Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

It is broadly agreed that Cubism started in 1908, with the works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They drew inspiration from many sources and on their way to Cubism created works in other style such as Impressionism, Symbolism, or Fauvism. Paul Cézanne in some ways could be called the grandfather of the style, as his works exhibited in Paris in 1907, a year after his death, were one of the major sources of inspiration. Yet another inspiration was Iberian sculpture and African art.

The term Cubism is thought to have originated from a comment by an art critic Louis Vauxcelles, who described Braque’s landscapes from 1908 as reducing everything to “geometric outlines, to cubes”. While this offhand comment is a great simplification, it is exactly the kind of simplification our minds love, so it caught on.

Analytical and Synthetic Cubism

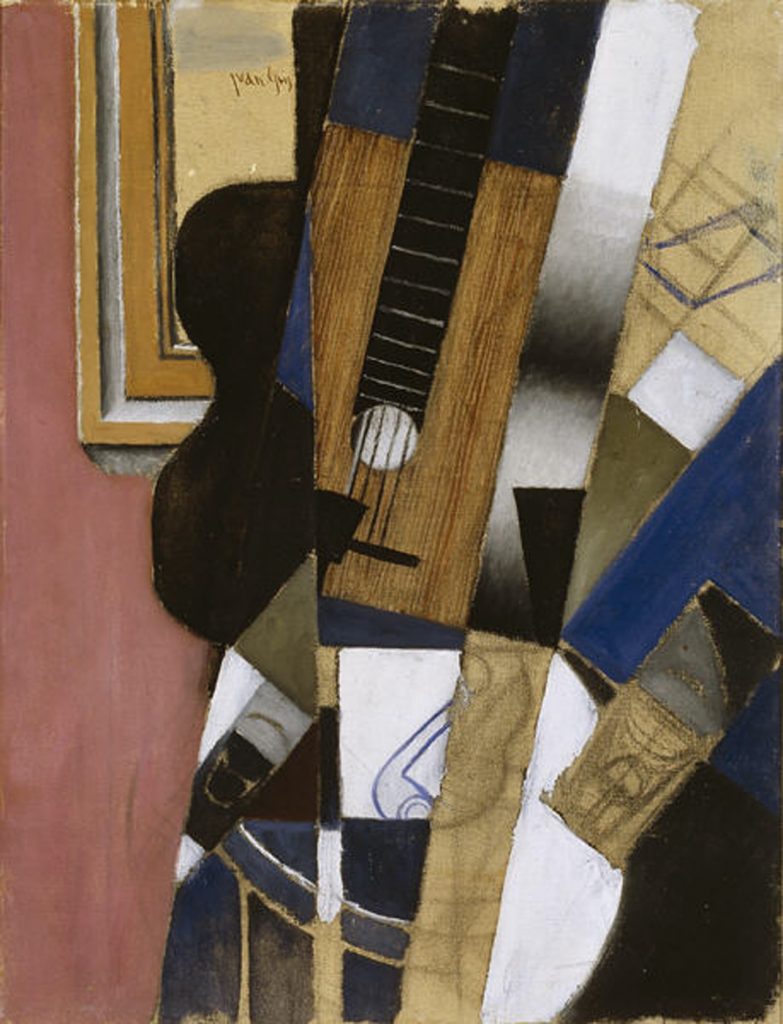

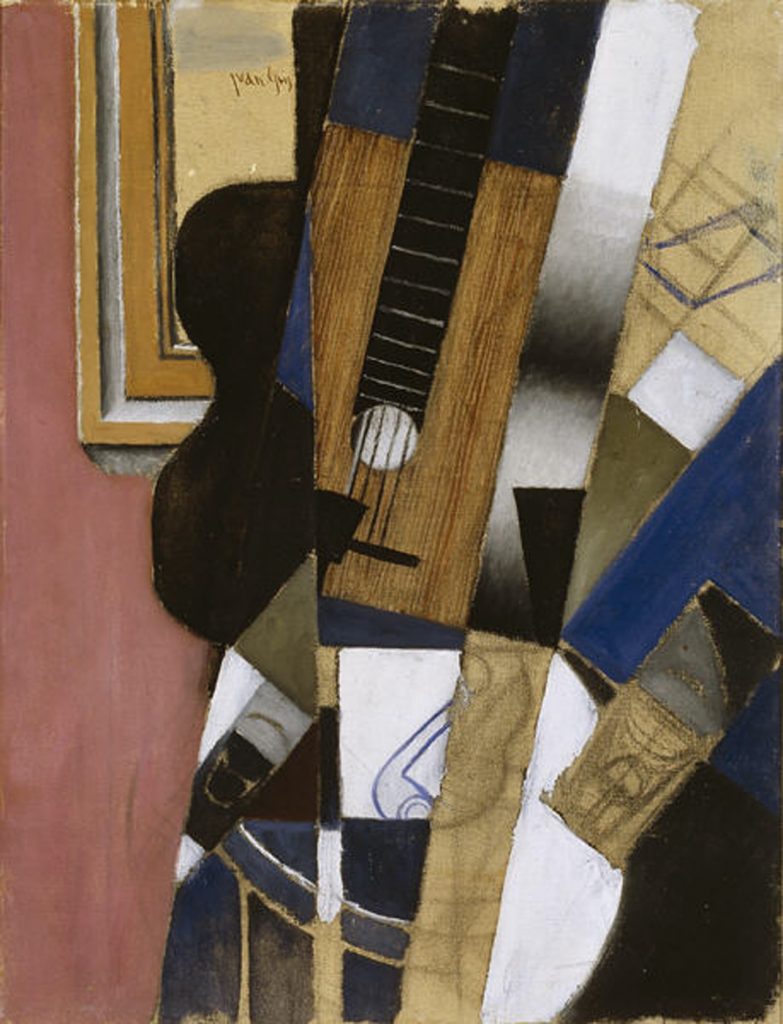

Cubism is typically divided into two phases: Analytical and Synthetic. The Analytical Cubism phase lasted from 1908 to 1912 and is characterized by a limited color palette, that allowed the artists to focus on the object. They would show multiple viewpoints of the object within the painting radically breaking with the ideal of linear perspective that has been the norm since the Renaissance. It feels like the artists are trying to explode the object onto the canvass, to accept the two-dimensionality of it and unravel the three-dimensional objects onto it to achieve a new level of order.

Here you can look at Georges Braque, La Guitare painting created in 1909-1910, now owned by Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom.

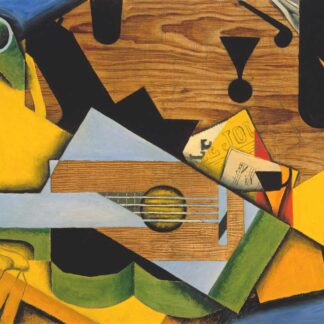

The Synthetic Cubism phase started in 1912 and “officially” came to an end in 1914 with the beginning of World War I. That of course did not mean Cubism ceased then, it was a style continued and adopted by new painters, but the initial exploration into the possibilities of the style was done by then and certain foundations have been agreed. Synthetic Cubism adopts a broader palette with many vivid colors, often used as accents. Painters abandon any illusion of shading but also simplify the forms, we can see that the two-dimensionality of the canvass now takes precedence and objects have to be simplified to conform to it. In this phase, artists also started experimenting with collage.

Juan Gris, Guitar and Pipe, 1913, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Unites States.

Places, Exhibitions, People

Sometimes a place can become a fertile ground for artistic innovation and that was certainly the case with Bateau Lavoir (Washhouse Boat). It was a building in the Montmartre district of Paris, previously a ballroom and a piano factory. The building has been squatted for artists’ studios and residences in 1889. Since then a succession of artists took residence, but it also became a meeting place for those who did not live there. In the early 20th century it was certainly a place to be if one wanted to be on the cutting edge of avant-garde. Residents and guests included artists, writers, and art dealers such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Marie Laurencin, Amedeo Modigliani, Maurice Utrillo, María Blanchard, Guillaume Apollinaire, Alfred Jarry, Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, Ambroise Vollard, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and Berthe Weill.

Bateau Lavoir, ca 1910, Montparnasse, Paris, France, source: Christies.

Ballets Russes, a ballet company created by Sergei Diaghilev was another place where artistic creativity could find an outlet. The company was created in 1909 in Paris and it toured Europe and the Americas until 1929. It created a beautiful environment for artists representing various arts to collaborate and throughout the years its sets and costumes were designed by artists that you will meet in this course, among others.

Natalia Goncharova, Design for the Curtain for Act III of Le Coq d’Or of Ballets Russes, 1914. Digital copy retrieved online: https://rptownsend.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/3413-218.jpg.

Another important ingredient of any new artistic movement is being able to exhibit. This was enabled initially by Salon des Indépendants, formed in Paris in 1884 by a group of Post-Impressionists. Advertised as “without jury nor reward” it allowed artists not accepted by the academy to show their works to more adventurous audiences. Braque was exhibiting there from 1906, the 1907 show was dominated by Fauvists, and 1908 already included some proto-Cubist works. Interestingly Picasso avoided exhibiting at the Salon, and so did Braque once he delved into Cubism, this led to an unofficial division of Cubist painters into Salon and Gallery Cubists. In this course, you will meet mostly the Gallery group.

By 1912 Cubists had their first international show in Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona and by 1913 they traveled across the ocean to New York to the famous Armory Show that presented the works of the European avant-garde and had deep repercussions for the American art scene (including fashion – a cubist dress became a thing), as well as opening a new market to European painters.

Armory Show, International Exhibition of Modern Art, the Cubist Room, 1913, source: Art Institute of Chicago.

Yet another thing that artists need like oxygen are art dealers and collectors. Especially since art liberated itself from the rigor of church and state commissions and ventured into the “art for art’s sake” territory the market started playing a significant role. Artists that signed up with galleries had easier access to the buyers, those who could find a rich patron were lucky, as were those who managed to build a name big enough to see their paintings flying off the walls. For others, life was a constant battle for attention and to make sure their works can be sold and they can support themselves. Given how experimental Cubism was it was a high-risk venture for sure.

Juan Gris, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1921, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

However, once again the Impressionists managed to slightly open the doors here, due to the commercial success of their paintings (though often after the artist’s death) collectors were now more open to snapping those risky avant-garde works early on to capitalize on them later. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was an art dealer that avant-garde artists were dreaming of, just as Leo and Gertrude Stein were such collectors. They had open minds and curiosity allowing them to explore radical art, they had money to buy it and most of all they had connections to help artists make their name.

Gertrude Stein Sitting on a Sofa in Her Paris Studio, 1930, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., United States.

As you can see all ingredients came together to enable the revolution that was Cubism. Let’s now meet some of the artists that made it happen.

- 10 min

What is Cubism and where did it come from?

Cubism is without a doubt one of the most important art movements of the 20th century. Where Impressionism started stepping away from the ambition of objectively representing the real world, Cubism took the whole notion and threw it out the window, breaking the glass in the process.

While not many artists persisted with the style throughout their careers it has been a stepping stone or gateway drug 😉 to further experimentation for many. The radical break that Cubism allowed became a door wide open to continue exploring ideas further and further away from representative art, all the way to complete abstraction. It is, however, worth remembering that Cubism itself never became a fully abstract style, no matter how many different viewpoints you can see in a Cubist painting they are still viewpoints of a real object you can recognize.

Here you can look at Georges Braque, Houses at L’Estaque painting created in 1908, now owned by Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

It is broadly agreed that Cubism started in 1908, with the works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. They drew inspiration from many sources and on their way to Cubism created works in other style such as Impressionism, Symbolism, or Fauvism. Paul Cézanne in some ways could be called the grandfather of the style, as his works exhibited in Paris in 1907, a year after his death, were one of the major sources of inspiration. Yet another inspiration was Iberian sculpture and African art.

The term Cubism is thought to have originated from a comment by an art critic Louis Vauxcelles, who described Braque’s landscapes from 1908 as reducing everything to “geometric outlines, to cubes”. While this offhand comment is a great simplification, it is exactly the kind of simplification our minds love, so it caught on.

Analytical and Synthetic Cubism

Cubism is typically divided into two phases: Analytical and Synthetic. The Analytical Cubism phase lasted from 1908 to 1912 and is characterized by a limited color palette, that allowed the artists to focus on the object. They would show multiple viewpoints of the object within the painting radically breaking with the ideal of linear perspective that has been the norm since the Renaissance. It feels like the artists are trying to explode the object onto the canvass, to accept the two-dimensionality of it and unravel the three-dimensional objects onto it to achieve a new level of order.

Here you can look at Georges Braque, La Guitare painting created in 1909-1910, now owned by Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom.

The Synthetic Cubism phase started in 1912 and “officially” came to an end in 1914 with the beginning of World War I. That of course did not mean Cubism ceased then, it was a style continued and adopted by new painters, but the initial exploration into the possibilities of the style was done by then and certain foundations have been agreed. Synthetic Cubism adopts a broader palette with many vivid colors, often used as accents. Painters abandon any illusion of shading but also simplify the forms, we can see that the two-dimensionality of the canvass now takes precedence and objects have to be simplified to conform to it. In this phase, artists also started experimenting with collage.

Juan Gris, Guitar and Pipe, 1913, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, Unites States.

Places, Exhibitions, People

Sometimes a place can become a fertile ground for artistic innovation and that was certainly the case with Bateau Lavoir (Washhouse Boat). It was a building in the Montmartre district of Paris, previously a ballroom and a piano factory. The building has been squatted for artists’ studios and residences in 1889. Since then a succession of artists took residence, but it also became a meeting place for those who did not live there. In the early 20th century it was certainly a place to be if one wanted to be on the cutting edge of avant-garde. Residents and guests included artists, writers, and art dealers such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Marie Laurencin, Amedeo Modigliani, Maurice Utrillo, María Blanchard, Guillaume Apollinaire, Alfred Jarry, Jean Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, Ambroise Vollard, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and Berthe Weill.

Bateau Lavoir, ca 1910, Montparnasse, Paris, France, source: Christies.

Ballets Russes, a ballet company created by Sergei Diaghilev was another place where artistic creativity could find an outlet. The company was created in 1909 in Paris and it toured Europe and the Americas until 1929. It created a beautiful environment for artists representing various arts to collaborate and throughout the years its sets and costumes were designed by artists that you will meet in this course, among others.

Natalia Goncharova, Design for the Curtain for Act III of Le Coq d’Or of Ballets Russes, 1914. Digital copy retrieved online: https://rptownsend.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/3413-218.jpg.

Another important ingredient of any new artistic movement is being able to exhibit. This was enabled initially by Salon des Indépendants, formed in Paris in 1884 by a group of Post-Impressionists. Advertised as “without jury nor reward” it allowed artists not accepted by the academy to show their works to more adventurous audiences. Braque was exhibiting there from 1906, the 1907 show was dominated by Fauvists, and 1908 already included some proto-Cubist works. Interestingly Picasso avoided exhibiting at the Salon, and so did Braque once he delved into Cubism, this led to an unofficial division of Cubist painters into Salon and Gallery Cubists. In this course, you will meet mostly the Gallery group.

By 1912 Cubists had their first international show in Galeries Dalmau in Barcelona and by 1913 they traveled across the ocean to New York to the famous Armory Show that presented the works of the European avant-garde and had deep repercussions for the American art scene (including fashion – a cubist dress became a thing), as well as opening a new market to European painters.

Armory Show, International Exhibition of Modern Art, the Cubist Room, 1913, source: Art Institute of Chicago.

Yet another thing that artists need like oxygen are art dealers and collectors. Especially since art liberated itself from the rigor of church and state commissions and ventured into the “art for art’s sake” territory the market started playing a significant role. Artists that signed up with galleries had easier access to the buyers, those who could find a rich patron were lucky, as were those who managed to build a name big enough to see their paintings flying off the walls. For others, life was a constant battle for attention and to make sure their works can be sold and they can support themselves. Given how experimental Cubism was it was a high-risk venture for sure.

Juan Gris, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1921, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France.

However, once again the Impressionists managed to slightly open the doors here, due to the commercial success of their paintings (though often after the artist’s death) collectors were now more open to snapping those risky avant-garde works early on to capitalize on them later. Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was an art dealer that avant-garde artists were dreaming of, just as Leo and Gertrude Stein were such collectors. They had open minds and curiosity allowing them to explore radical art, they had money to buy it and most of all they had connections to help artists make their name.

Gertrude Stein Sitting on a Sofa in Her Paris Studio, 1930, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., United States.

As you can see all ingredients came together to enable the revolution that was Cubism. Let’s now meet some of the artists that made it happen.